The war-fighting domain is increasingly extending into space. With it come new applications of a familiar authoritarian playbook: salami-slicing of red lines, service disruption, intimidation – and plausible deniability. Welcome to the age of greyzone space operations.

“Space is, in many ways, the ideal domain for greyzone operations and activities, because there are a lot of things you can do that fall below the threshold of overt conflict,” Todd Harrison, a Senior Fellow at the American Enterprise Institute and expert on defence and space policy, told Resilience Media. “You have a whole suite of non-kinetic forms of space attack that can and have been used without triggering escalation or overt conflict.”

Experts highlight a broad range of space capabilities that could be used for greyzone activities.

One category is electronic, targeting satellites as information systems. It includes cyberattacks, radar jamming and interference in GNSS systems like GPS.

Low-intensity laser or energy capabilities on the ground or in orbit can be used to “dazzle” the cameras on satellites, temporarily disrupting imaging or reconnaissance capabilities – perhaps without causing permanent damage.

Katherine Melbourne, a policy analyst in the Center for Space Policy and Strategy at The Aerospace Corporation, told Resilience Media: “these ‘lower level’, more temporary attacks that don’t permanently take out a satellite, [they] would be considered harder to respond to.”

Then there’s a whole range of possible orbital manoeuvres – an area China in particular is exploiting as it gets more active in space exploration.

Chinese experimental satellites have been tracked engaging in various kinds of advanced rendezvous and proximity operations (RPO). These kinds of satellite manoeuvres are sometimes compared to dogfights, but “it’s more like slow-motion ballet,” argues Harrison.

For example, an adversary satellite – including an ostensibly commercial satellite – could manoeuvre close to a military or other satellite. From there, it could do a visual inspection. “Just by looking at it, [they] can pretty much determine whether there is also ASAT capability”, said Holmes Liao, a former distinguished adjunct lecturer at Taiwan’s War College.

Liao added that nearby satellites can pick up a much stronger radio frequency signal, meaning the data can be collected – though if it’s encrypted they can’t necessarily decipher it. With advances in quantum computing, some experts think that could change in the coming years.

Space wargames have considered other moves such as positioning satellites to block an opponent’s access to key orbital slots.

Supposedly innocent space systems such as weather or commercial communications satellites could be used for such strategic purposes. Debris removal satellites could be used to redirect debris towards an enemy satellite, with plausible deniability.

It appears that the functionality of the satellites being launched into space is continuing to grow. In January 2022, a Chinese SJ-21 satellite disappeared from its regular orbit and then moved alongside a dead Chinese BeiDou satellite – the country’s competitor to GPS – shifting the BeiDou satellite from geosynchronous orbit into a graveyard orbit.

Earlier this year, Chinese satellites demonstrated what is believed to be a refueling operation in geosynchronous orbit.

“A lot of the satellites in geosynchronous orbit are large, exquisite,” explained Melbourne. “It’s expensive to get to geosynchronous orbit, and so having refueling capability would allow to extend the life of these missions, but it would also potentially allow for additional manoeuvre capability.” This could be used to inspect a satellite, or move into close proximity to it, she added.

Using greyzone tactics against Taiwan: ‘A relatively bloodless war’

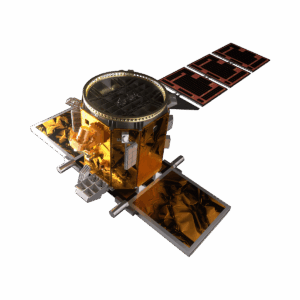

One country thinking through the implications of greyzone space operations is Taiwan, which currently has a small number of its own satellites but is rapidly ramping up its space programmes. It faces a foe with probably the most varied and advanced anti-satellite capabilities of any country.

So what would be the aim of using greyzone tactics against Taiwan?

“There are tons of reasons”, says Dr Sheu Jyh-Shyang, an assistant research fellow at INDSR, the Taiwanese defence ministry’s think tank, though the views expressed here are his own. He highlights two as particularly important. One is sabotaging critical infrastructure, which would undermine social stability, damaging the reputation of the Taiwanese government and the morale of the Taiwanese people.

Another is to test resilience and reactions, to see if China can cross any red lines without a robust response.

“They want to know how fast [Taiwan] can fix that, or which kind of reaction [they see] when that happens,” he says.

To see what such tactics would likely target, it’s useful to split what Taiwan uses space for into PNT (GPS), communications, and monitoring (including imaging and weather).

If the aim is to shake public confidence in the government, GPS jamming would be likely. This would cause disruption to navigation in key shipping lanes around Taiwan. Jamming signals across the main island – which experts say is well within China’s technical capabilities – would cause disruption to critical infrastructure from the stock market to the grid, all of which rely on GPS signals in some form for timing synchronisation.

Another likely target is communications satellites. Following a spate of incidents – linked to China – in which subsea cables have been damaged in Taiwan and elsewhere, “there’s an urgency in Taiwan for us to develop satellite communication capabilities,” said Holmes.

Building more resilience in space

Starlink-like low Earth orbit (LEO) constellations offer a degree of redundancy in case of serious damage to undersea cables.

Wargames have envisaged a campaign coordinating significant damage to several critical undersea cables connecting Taiwan to the world with a related attempt to disable Taiwan’s space-based communication systems. The author of one concluded: “With [ground and undersea cable systems] and Taiwan’s space-based communication systems disabled, China could conceivably absorb Taiwan in a relatively bloodless war.”

If China wanted to damage Taiwan’s connectivity, they could simultaneously damage subsea cables and space assets. In that case, “this kind of greyzone activity might be conducted, and it will really cause a lot of damage,” says Dr Sheu.

As infrastructure – everything from the grid to hospitals – becomes more reliant on internet connectivity, “to protect the connectivity is becoming a crucial issue for us,” he says.

Without the subsea cables, Dr Sheu reckons that Taiwan still has enough connectivity through satellites to meet its basic infrastructure needs, meaning that China would have to successfully disable Taiwan’s satellite connectivity to fully cut it off. For now, that is likely to be difficult.

Taiwan has partnered with the British-French company Eutelsat OneWeb – which since October 2024 has provided 24/7 satellite coverage – and SES, which operates geostationary and medium earth orbit (MEO) satellites.

Dr Sheu notes that this combination increases resilience, because an attack on it would require coordinated moves in multiple orbits. But Taiwan is still looking for additional partnerships, he said. “We want to create more redundancy and much more resilience for the entire system”.

Ultimately, Taiwan aims to have a sovereign LEO satellite constellation of roughly 120 satellites. It plans to launch its first sovereign LEO satellite in 2027, the first of six satellites in a “pathfinder programme.” Private companies would then be contracted to produce these at scale once the technology has been demonstrated.

But in the meantime, Taiwanese analysts are generally optimistic that commercial companies like OneWeb could be relied upon in a crisis.

Under Taiwanese law, telecom companies operating in Taiwan have to be majority Taiwanese-owned – which rules out Elon Musk’s Starlink, a subsidiary of SpaceX. At the same time, China has little leverage because such companies are not allowed to operate in the Chinese market, argues Dr Sheu.

Still, the sheer number of satellites in the constellations from which Taiwan leases bandwidth makes them as a whole resilient to attacks, even if individual satellites are vulnerable.

A recent Chinese research simulation concluded that it was technically possible to jam Starlink across all of Taiwan for twelve hours. But to do so would require a minimum of 935 synchronised airborne jammers.

Dr Thomas Withington, a RUSI Associate Fellow, said, “Technically, it’s possible to jam everything, but it’s actually really difficult in some cases, and demands a particular skill set and technology in certain cases.”

Starlink has proven to be a generally robust system for Ukraine, and experts argue the commercial operators of the communications satellites that Taiwan currently uses would likely be able to respond quickly to any electronic attacks for similar reasons. With software-defined radio (SDR), engineers on the ground can quickly upload patches and fixes to satellites as countermeasures.

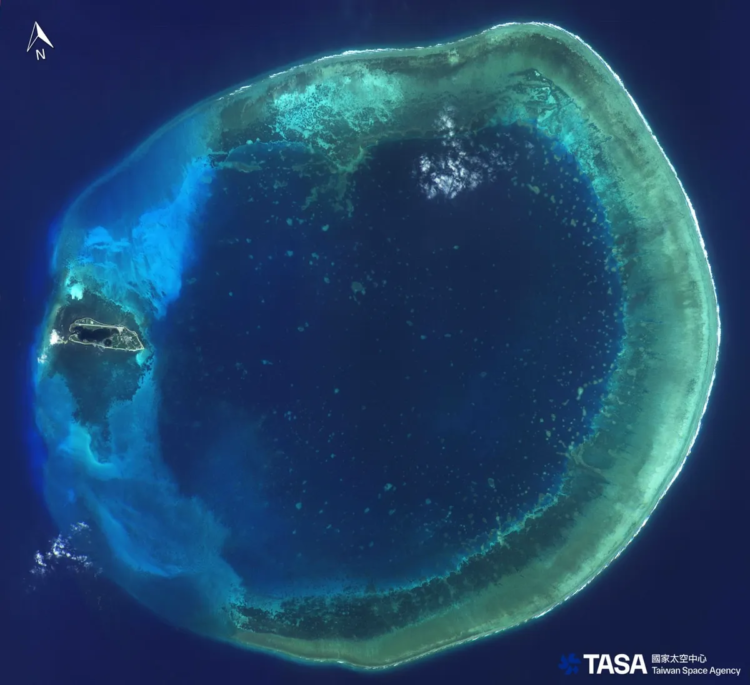

Another important capability is high-resolution imaging satellites, which have many applications including military. Last month, Taiwan launched its first FORMOSAT-8 optical satellite, which offers much higher resolution observation than earlier capabilities. The next-generation Formosat-9, the first of which is slated for launch in 2028, has synthetic aperture radar (SAR) technology, which uses microwave radar to build images and is less impacted by weather conditions, particularly cloud cover.

The two systems offer “a significant increase in data availability will allow Taiwan to respond to threats—both natural and military—based on near real-time information,” according to a CSPS report.

It highlighted in particular “SAR technology will allow Taiwan to observe and assess activity patterns at Chinese military and nuclear sites, regardless of time of day or weather.”

Dr Sheu also argues that “China might also claim that the Earth observation satellite is doing some spy operation and so on and try to sabotage [it]… this is also the reason that we need to have a real situation awareness capability to protect our own satellite.”

Experts often point to the vulnerability that comes from Taiwan’s limited space domain awareness. Detection of operations in space is difficult meaning that, as Dr Sheu has written, “awareness of the space domain is essential to ensuring resilience and responsiveness”.

Dr Sheu says that “if any of those satellites, or even debris, could collide with the Taiwanese satellites, then we need to know about it.” Also Taiwan needs to be aware of when a Chinese spy satellite is collecting imagery over Taiwan. “When it passes over certain locations, then Taiwan’s military may need to hide [their equipment].”

Melbourne said that Taiwan relies on information from allies and partners to be able to know what’s going on in orbit. “There’s open source datasets that [Taiwan] can use,” she added. “But as far as anything threatening their satellites, that information would come from outside of Taiwan.”

Taiwanese analysts have called for Taiwan to boost its space domain awareness capabilities, such as through closer collaboration with partners like Japan.

Along with satellite development, Taiwan’s space agency (TASA) is working on improving its space domain awareness with a new centre to process data needed to identify and interpret satellite manoeuvres, and a new space-based radar partnership with LeoLabs.

Using information from commercial entities, non-profits and ESA, “we aggregate them together and provide a better picture of space situational awareness and space domain awareness,” said one analyst, though adding that some ground radar and ground telescopes would be needed, too.

The country’s sovereign satellites face an additional challenge unique to Taiwan: lawfare. Satellites are supposed to be registered with a UN body. But as Dr Crystal Tu, an assistant research fellow at INDSR, has written, Taiwan’s exclusion from the UN – with the PRC claiming sovereignty over it despite never having ruled it – means that its satellites are officially registered as PRC satellites.

That opens them up to possible lawfare: legal challenges that claim Taiwan’s de facto satellites to be the PRC’s.

An important additional possible use for greyzone tactics would be to deter allies from coming to Taiwan’s aid.

A wargame last year highlighted the importance of increasing awareness even among policymakers of America’s options to similarly temporarily disable enemy space capabilities in a deniable manner.

In another wargame from 2022, Chinese space debris removal satellites were moved close to American military satellites in LEO; others have considered similar moves around Japanese space assets.

China “could use lasers to blind the sensors on [our] satellites – like our missile warning satellites – and other non-destructive means to attack and degrade US military or commercial space systems,” said Harrison. “[It’s] a way of warning the United States: don’t get involved in this.”