There are multiple thousands of kinetic and battle-ready drones being produced for use in Ukraine every month, but not just by Allied countries – by adversaries, too. Whatever use they will have in future active combat beyond Ukraine, that drone race is putting a spotlight on startups building protection against incursions. In one of the latest developments, Frankenburg — a startup building low-cost, AI-based anti-drone missile systems — is ramping up, and to fuel that growth, Resilience Media has learned that it has raised capital approaching $50 million at a valuation of around $400 million.

Multiple sources say the round is closed and will be announced soon. The funding is bringing in a slate of new investors, they added, and may lay the groundwork for a bigger round possibly as soon as later this year. Current backers of the startup include London’s Blossom Capital, Shellona Ltd, Estonian private equity firm MM Group, and the CEO of Milrem Robotics, Kuldar Vaarsi.

Big investors and supporters of defence tech in Europe have included General Catalyst and Plural, both of which declined to comment for this story.

Other investors that Resilience Media contacted explicitly said they were not involved in the round.

Kusti Salm, the CEO of Frankenburg, declined to comment for this story. We will continue to update this story as we learn more.

The investment is not only an important milestone for Frankenburg; it also underscores some bigger themes in defence technology moving into 2026.

Why counter-drone technology?

Frankenburg, based across Estonia and Latvia, was started in early 2024 after prominent Baltic technology founders and investors got behind the idea of building fast-to-produce, cheaper anti-drone missile systems specifically in aid of Ukraine.

But in the two years since, drones have grown more sophisticated; swarm-based use has become more commonplace in the war-torn country; and unwelcome drones and other objects are increasingly appearing in other countries’ airspace. And so more countries have started to think more about how to arm themselves with more updated defence technology against drone incursions on their own territories.

That has led to more attention for a range of companies. Some take a “soft-kill” (software-based) approach using radio magnetic spectrum. Some like Frankenburg build hardware and software – others in the space include Latvia’s Origin Robotics and LMT; Estonia’s DefSecIntel Solutions; and Atreyd from France – and these approaches range from missile systems like Frankenburg’s to concepts for “drone walls”.

Frankenburg’s moment

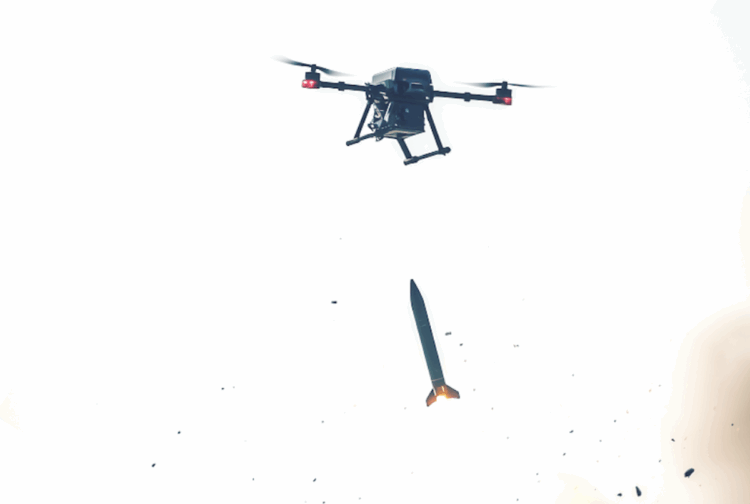

A round of this size at this valuation is a big step for Frankenburg. The startup has to date disclosed less than $5 million in seed funding, according to PitchBook data, with a post-money valuation of around $161 million (€160 million). But with the bigger focus on counter-drone systems, it’s found momentum. Frankenburg has used the modest amount it has raised so far to expand its geographical footprint (such as this UK headquarters established in December 2024) and build and test its systems (it showed off this Shahed interceptor in Latvia in December 2025). Earlier in January, it announced a partnership with Babcock, the UK prime, to develop a maritime counter-drone system to protect ships, ports and off-shore assets.

Frankenburg’s star bench

For a Baltic defence startup, Frankenburg has an impressive network of people connected to it.

Taavi Madiberk — who is credited as the (sole) co-founder and is now the company’s non-executive chairman — is also the CEO and founder of next-generation energy storage/battery startup Skeleton Technologies. Martin Herem, an Estonian retired military commander, is an advisor. Milrem Robotics’s Vaarsi is also a board member in addition to strategic investor. And Salm, who joined as CEO in September 2024, has a pretty impressive resume, too: he’s currently a director at the NATO Innovation Fund (itself a prominent defence tech investor) and he was previously the permanent secretary in Estonia’s Ministry of Defence, among other roles.

This raft of people has helped the company launch, and has likely opened funding doors.

The funding climate remains hot for defence startups

Last year saw a record amount of money get channeled into startups in defence and the wider category of resilience, which, depending on how you cut it, was between $49.1 billion (PitchBook) and a more conservative $7.1 billion (Crunchbase).

This is due to multiple reasons: the geopolitical threat climate; the evolving technology of weapons; and the changing military mindset around accessing startups to stay on top of that innovation. All of this has led to more willingness and money to fund defence tech, and an easier route for bidding for and winning contracts.

Salm telegraphed as much during an interview at Resilience Conference last year, where he noted how bids have become significantly more compressed, while money availability has expanded.

It’s the “first time in 70 years we are in this situation, where there is private money available for developing defence technology and weapons,” he said on stage.

Meanwhile, business development has massively shifted.

“Conventionally the way the defence market works is that the customer comes in with their requirement,” Salm continued. “And the requirement is not a drawing on a whiteboard. It’s 800 pages of spec.” These days, you are more likely to see founders playing a role in defining requirements, he said. Speed of production, affordability and a flexible approach to “minimum viable product” are all considered.

One small cloud…

Some believe that the enthusiasm and disruptive new approaches may be resulting in too much haste. “We hear their product is not really performing that well and their commercial traction and revenues are not that great,” grumbled one investor when asked about the company. Others, clearly, disagree.