In a new report from the Munich Security Conference, the message is blunt: wrecking-ball politics, led by a belligerent American regime, is changing the face of Europe’s defence.

“However one may assess the foreign policy of the current US administration, one thing is clear: It is already changing the world, and it has triggered dynamics whose full consequences are only beginning to emerge,” writes Wolfgang Ischinger in the foreword. Among other things, Ischinger is a former German ambassador to the US, and the previous chairman of the MSC, taking place this week. His experiences inform his words. He frames this year’s report around a basic break with what US allies assumed for generations: not only American power, but a shared set of principles behind the post-1945 order. That shared base now looks far less certain, and the report argues the implications for Europe, and for transatlantic cooperation, are hard to overstate.

“The world has entered a period of wrecking-ball politics,” the report notes, with sweeping destruction, not careful reform, becoming the default move. More than 80 years after construction began, the US-led post-1945 international order is now “under destruction,” with the current US administration presented as the most prominent actor promising to break free of the old order’s constraints and rebuild something stronger on the other side.

The report goes further and makes the political claim explicit: in many Western societies, forces “favoring destruction over reform” are gaining momentum.

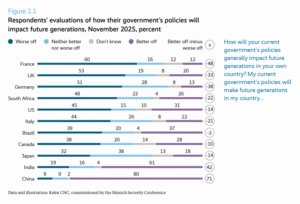

“In all G7 countries surveyed for the Munich Security Index 2026, only a tiny proportion of respondents say that their current government’s policies will make future generations better off. And both domestically and internationally, political structures are now perceived as overly bureaucratized and judicialized, impossible to reform and adapt to better serve the people’s needs. The result is a new climate in which those who employ bulldozers, wrecking balls, and chainsaws are often cautiously admired if not openly celebrated,” the report’s authors write in a stunning confirmation of the current crop of micro-despots and populists that are popping up like toadstools throughout Europe.

Further, where this turns into a European problem is clear. The report says the US administration’s turn away from core parts of the existing order is already hitting Europe in visible ways. It points to a Russia that is “regaining tactical initiative” along parts of the front in Ukraine, and intensifying hybrid warfare across Europe, while Washington’s gradual retreat, wavering support for Ukraine, and even threatening rhetoric on Greenland heighten Europe’s sense of insecurity.

In that context, the report says the US approach to European security is now seen as volatile, shifting between reassurance, conditionality, and coercion, leaving European states trying to keep Washington engaged while also preparing for greater autonomy. Further, this is a call to action. The report calls for a rearming and rebuilding of Europe’s defences, and that requires shared technology that can handle both peace and, when the time comes, war.

A Sad World

First, we learn that the world is in a bad way. The report doesn’t pull any punches. Starting with the image of Trump tearing down the East Wing of the White House, it goes on to associate this destructive style with the new American outlook in general. The snark, shall we say, is prominent:

For Trump’s critics, the project is likewise symbolic. They see it as a near-perfect metaphor for his assault on long-standing norms, his disdain for due process, and his treatment of the presidency as personal property. Some noticed another Trumpian trademark in an early model of the new East Wing that featured colliding windows and a staircase without a clear landing.

The authors expand this metaphor to speak of an America overrun with hardcore nationalism and a thundering disregard for norms. The result of this shift is that Europe must rethink how it defends itself and its allies.

The report, for the most part, repeats the same notion that European security once rested on American power and a shared set of assumptions about how the world should work. That shared baseline no longer holds. US power still exists, but the political logic behind it is unstable. Commitments feel conditional, and elections reset priorities fast, especially given the potential instability of the November midterms. What used to be implicit now has to be renegotiated, again and again.

The report ties this directly to the public mood inside democracies. Distrust runs deep, and disenchantment is widespread. Western Europeans feel their children will be worse off in the future, with France reporting 60 percent of its citizens feeling despondent, while the UK and Germany report 53 and 51 percent, respectively.

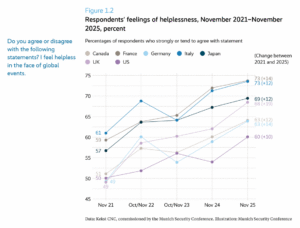

It gets worse. “Moreover, many people perceive their political systems and international institutions as incapable of addressing mounting global risks – be they climate change or communicable diseases – and of managing the challenges that come with economic transformations and technological changes,” they write.

Further, global citizens feel more “helpless in the face of global events” than ever, with Canada and France reporting 73 percent and the US rising from 50 percent in 2021 to 60 percent today. This despair is indicative of wider trends of political polarization, disinformation, racism, and antisemitism rising in the West. Europe, for her part, knows the costs of war far better than any modern American — barring a veteran of the U.S.’s quixotic efforts in the Middle East. The drums beating on the Ukrainian border are enough to make anyone anxious.

The Kantian Triangle

The report goes on to comment on the destruction of the Kantian Triangle of Peace, a post-War concept that describes “first, the belief that multilateral institutions and universal rules enhance rather than constrain US power; second, the conviction that an open international order and economic integration serve US prosperity and security; and third, the assumption that democracy, human rights, and close cooperation among liberal democracies are strategic assets and should guide US foreign policy.”

The Trump administration treats the postwar order as a constraint and, as the US National Security Strategy puts it bluntly, its goal is to restore the “primacy of nations” and push back against what the White House calls “sovereignty-sapping incursions” by international bodies. These include, presumably, the EU itself, a group that symbolizes death by bureaucracy and a slavish devotion to austerity and rules. The US, like the cheesemaker bothered by Brussels’ hygiene requirements, wants to be free.

That view has echoes in an earlier America, the one that came before Pearl Harbor.

In the 1920s and 1930s, the United States saw itself as strong precisely because it stayed apart. Congress rejected the League of Nations, and trade barriers went up. Foreign entanglements were treated as traps, and the national goal was defined as freedom of action, not shared burdens. Security meant oceans on both sides and no standing commitments abroad.

The Trump administration’s language fits that tradition. It assumes the world is competitive, states act alone, and cooperation is a cost to be minimized. The other difference between the 1920s and today is scale. Pre-war America could still plausibly stand back. Today’s United States sits at the center of every system it is trying to escape.

Further, the Trumpian view pulls nation-states back to the foreground. It rejects the assumptions that dominated the post-Cold War years, especially those laid out in The End of History and the Last Man, where Francis Fukuyama argued that Western-style liberal democracy was not just a winning system but the final one, the political endpoint toward which all successful societies would eventually move. The Trump worldview cuts against that idea and treats history as open-ended and conflict-driven. It assumes that culture, borders, and power still matter more than convergence or universal values.

This has all been a long time coming. After the first Trump presidency, apocalyptic and totalitarian thought came to the fore, primarily in the aftermath of COVID-19. In a world where everything was unraveling, both the Left and the Right — for vastly different reasons — saw the rigid hand of dictatorship choking their democracies.

The gist of the report is simple: liberal democracies worked best when they worked together. That consensus is gone. The Trump administration now argues that those assumptions boxed the United States in, leaving it to bankroll systems that no longer serve “American interests.”

You can see the shift in the language of strategy documents and in the choices that followed. International institutions are no longer framed as unalloyed goods and, from a military standpoint, force multipliers. One internal memo described parts of the global governance system — namely the World Health Organization and the Paris Climate Agreement — as “dominated by progressive ideology.” Another warned against spending “taxpayer dollars” on what it called “globalist agendas.”

The result has been a rapid thinning of US participation. By January 2026, the White House issued a directive to withdraw from dozens of international bodies, arguing that they failed a basic cost-benefit test. Officials said some organizations needed to “adapt, shrink, or die.”

That logic did not stop at climate or health. Humanitarian and development institutions felt it too. The administration insists that the United States remains “the world’s most generous nation,” yet it shuttered USAID early in the term, a move that aid workers say created immediate gaps. One former official described the impact as “felt everywhere, all at once.”

The administration still backs institutions it sees as directly aligned with national security, including select UN agencies and the International Atomic Energy Agency. The point is not isolation. Cooperation is acceptable when it is narrow, transactional, and clearly subordinate to US sovereignty.

Diplomacy itself has also changed shape. While China has expanded its global footprint and now operates more diplomatic missions than the United States, Washington has gone the other way. Hundreds of career foreign service officers were pushed out. Ambassador posts sit empty. Project 2025 authors described the State Department as part of a “deep state” that needed to be cut down to size.

The Trump administration’s wager is that power flows from independence, not integration. The same can be said for the politicians in Hungary and Poland, and who can forget Brexit, a decisive blow to modern Europe if there ever was one. Whether that bet pays off is an open question. What is clear is that the old framework, the one that guided US strategy since 1945, no longer applies.

The Way Forward for Europe

The experts featured in this report are aligned with one thing: 2026 has to be a year of construction, not nostalgia. That the old order is not coming back, and pretending otherwise is a fool’s errand.

Here are the points made in the report for Europe (and the rest of the world) to heed as we enter an uncertain era. The boil down to one concept: agency over anxiety.

Europe must act as a real security provider, not a dependent.

“The era in which Europe could rely on the US as an unquestioned security guarantor is over. European leaders must accept this reality and act accordingly,” they write. European states need to move from incremental defense spending increases to coordinated capability building, especially in air and missile defense, drones, cyber, intelligence, and logistics. This includes serious defense industrial consolidation and faster procurement, not just bigger budgets.

Ukraine must be anchored irreversibly in Europe.

Experts agree that any pause in fighting cannot be treated as peace. Ukraine needs binding security guarantees, sustained military support, and rapid progress toward EU accession. “Robust, legally binding security guarantees will be essential to deter renewed Russian aggression following a potential ceasefire,” said the authors. “EU members will have to commit significant political and economic capital to enable Ukraine to swiftly meet the requirements for EU accession, anchoring its security within Europe’s legal and institutional order.”

Rules-based institutions must be fortified, not mourned.

The report repeatedly warns against nostalgia. Experts argue that defenders of the international order need to reinforce key institutions, reform them where possible, and show they can still deliver real outcomes. “In an era of wrecking-ball politics, those who simply stand by are at constant risk of entombment,” they write. “And given the amount of demolition already happening, it is no longer enough to only engage in reactive, small-scale efforts to reconstruct the old status quo. Those who oppose the politics of destruction have to fortify essential structures, draw up new, more sustainable designs, and become bold builders themselves. Too much is at stake. In fact, everything is at stake.”

All of this matters for security because alliances rest on confidence and capability. For decades, Europe had the first but not the second, leaning on vague promises of support written in the rubble of Berlin and London and later reinforced in the confident corridors of Washington. Europe now faces a colder reality. The United States may still show up, but that outcome can no longer be treated as automatic. Planning has to assume delay, friction, and divergence. The most troubling point, as the authors note, is that this shift is already underway, whether leaders admit it or not. The conclusion is hard to avoid. By 2026, Europe is entering a period of renewal and change, with or without its largest ally.